Workers, Workplaces, Sorting and Wage Dispersion in Mexico

Published:

In most countries, wage dispersion has recently increased, drawing researchers’ and policymakers’ attention. The dispersion in wages can be due to various reasons. For instance, it may come from differences in worker characteristics such as education or skills. However, even if people have the same characteristics, their wages can vary depending on the company they work for. More productive companies may pay higher wages, and these differences in productivity also contribute to wage dispersion. It could even be the case that workers with characteristics associated with high salaries tend to be employed by companies that pay high wages, a phenomenon known as positive assortative matching.

In a recent article with José Nuño-Ledesma, forthcoming in Economia, we study wage dispersion in Mexico, breaking it down into components associated with the reasons described: individual characteristics, company characteristics, and selective matching at both the national and regional levels.

Methodology

We model the wages of person $i$ in month $t$ using a linear regression with bidirectional fixed effects:

\[\ln(wage_{it}) = \alpha_i + \psi_{J(it)} + X'_{it} \beta + r_{it}\]The worker fixed effects $\alpha_i$ remain constant over time and capture individual characteristics that receive the same compensation across companies, such as skills or education. The workplace effects $\psi_{J(it)}$ capture the wage premium for all workers employed at the same workplace $J$. The vector $X_{it}$ contains observable characteristics of the individuals, and the term $r_{it}$ represents a residual. We estimate the model using social security data from the Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS) for 2004 to 2018 in five-year intervals.

With this model, we decompose the variance of wages as follows:

\[\operatorname{Var}\left(\ln \text{wage}_{it}\right)= \underbrace{\operatorname{Var}(\alpha_{i})}_{\text {workers }} + \underbrace{\operatorname{Var}(\psi_{\textbf{J}(it)})}_{\text {workplaces }} + 2 \underbrace{\operatorname{Cov}(\alpha_{i}, \psi_{\textbf{J}(it)})}_{\text {sorting}}) + remainder.\]Hence, a part of the wage variance is due to wage dispersion resulting from differences in worker characteristics, another part to dispersion in company wage premiums, and a third part to the extent to which the matching between workers and companies affects wages. When the covariance between company and worker effects is positive, high-wage workers (with a high $\alpha_i$ value) work at companies that pay high wages (with a high $\psi_J$ value)

Results

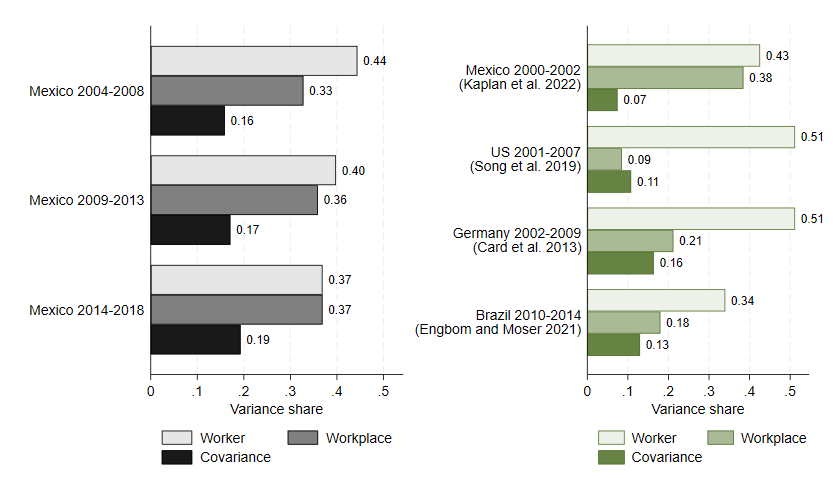

On the left panel of Figure 1, we show the results of the wage variance decomposition for men aged 25 to 54. The contribution of the individual components decreases over time, from 44% in 2004-2008 to 37% in 2014-2018. In contrast, the importance of the company components and selective matching has increased over time. When comparing 2014-2018 with 2004-2008, company effects account for about four percentage points more of the wage variance, and the covariance associated with selective matching accounts for about three percentage points more.

On the right panel, we show analogous variance decomposition results for wages in other countries. The contribution of company-level factors to wage dispersion in Mexico is higher than in the United States, Germany, and Brazil.

Figure 1. Wage Variance Decomposition

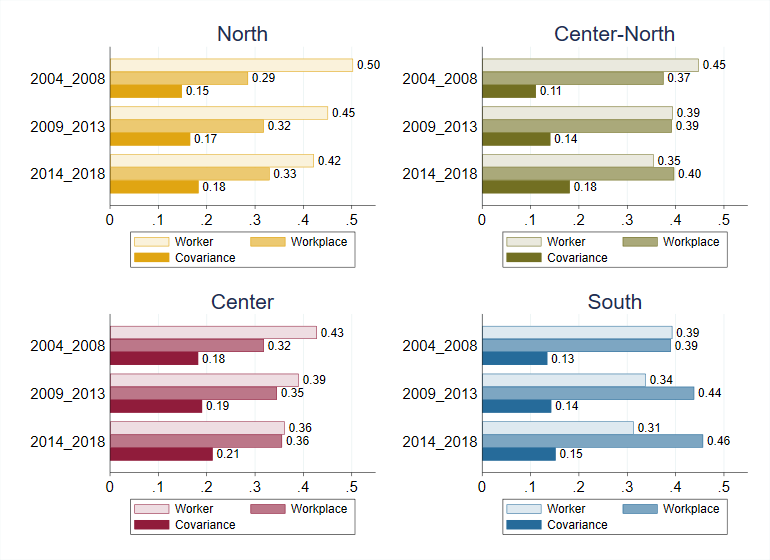

Figure 2 shows how the worker, firm, and covariance components contribute to wage dispersion across the country’s four regions. The contributions of each element to wage dispersion in the regions follow the same trend over time as the contributions at the national level.

Figure 2. Estimated Contributions to Variance by Region and their Change over Time

The contribution of firm effects to wage variance correlates negatively with regional GDP per capita. Firm effects are relatively more important in determining wage variance in the South, followed by the center-north, the central region, and finally, the North region. The article shows that this pattern is also present among states.

Assortative matching has a higher contribution to wage dispersion in the northern and central regions of the country. Our analysis shows that within each region, the contribution of selective matching to wage dispersion is greater in larger companies.

The tools for analyzing wage dispersion in Mexico presented in this paper are a starting point for future research on wages in the country. It will be interesting to examine how recent labor market reforms and changes associated with the pandemic have affected the contribution of wage dispersion determinants.